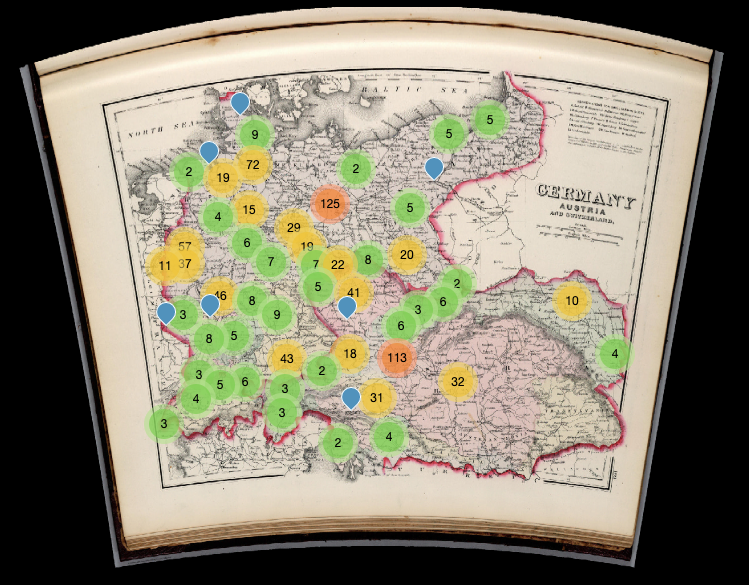

This interactive map plots the performances of African-American singers, dancers, and instrumentalists in the German lands up to the First World War. Click on the image to go directly to the map, where you can filter the results by year, zoom in and out to see which cities or regions had the most performers at different times, and find more details about the performances. When you click on a marker, a pop-up window will provide further details, including names, locations, venues, dates, and images where available. I have also listed some sources that confirm the performance: click here for the unabbreviated list of sources. These lists are not comprehensive but rather provide a starting point for further research. If you would like more sources on any of the performers, I am happy to provide that on request.

Jeff Bowersox

Context

We are generally familiar with the presence of Black musicians and dancers during the interwar period, when jazz became both an international sensation and a topic of considerable debate in the German lands. But African-American entertainers had appeared on German stages as early as 1856, and the brief stint by George Hicks’s Georgia Minstrels in Hamburg in 1870 marks the first Black-managed company of Black performers in central Europe. These early tours do not seem to have made a lasting impression, but the tours of the Fisk Jubilee Singers (right) and Jarrett and Palmer’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin Company in the late 1870s made a significant impact on German and Austrian audiences.

We are generally familiar with the presence of Black musicians and dancers during the interwar period, when jazz became both an international sensation and a topic of considerable debate in the German lands. But African-American entertainers had appeared on German stages as early as 1856, and the brief stint by George Hicks’s Georgia Minstrels in Hamburg in 1870 marks the first Black-managed company of Black performers in central Europe. These early tours do not seem to have made a lasting impression, but the tours of the Fisk Jubilee Singers (right) and Jarrett and Palmer’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin Company in the late 1870s made a significant impact on German and Austrian audiences.

They demonstrated that there was a ready audience for performances of American Blackness, represented both by spirituals (Fisk) and by minstrel song and dance (Jarrett and Palmer). Although these groups were managed by white impresarios and Jarrett and Palmer’s company presented African Americans in an unflattering light, the Black performers nevertheless confounded audiences’ expectations. Their mastery of concert singing and the inventiveness of their modern music and movement presented a striking contrast to the images of Blackness presented in ethnographic “people shows” [Völkerschauen] as well as in the blackface minstrel shows that were popular in large cities at the time.

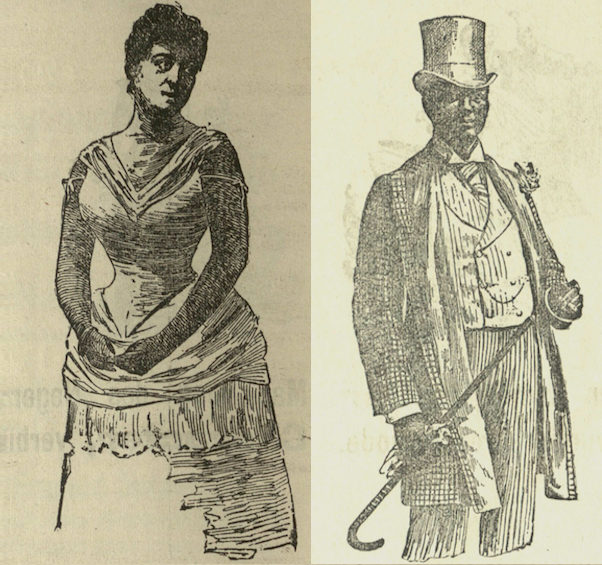

The successes of these troupes laid the groundwork for later groups, like Foote’s Afro-American Company in 1891 (including Marie Selika and Samson Williams, at left) and the Black America Company in 1896. These were also organized by white impresarios, but all of these large troupes provided immediate opportunities for members to take control of their own performing. Already in the early 1880s but more regularly from the late 1890s, there was an ever-increasing number of smaller groups of African-American performers circulating around and through the German lands. Their popularity increased along with the popularity of American music and dance forms after the turn of the century, as many of these were associated with African Americans. By 1914, Black entertainers were a frequent presence in major cities like Berlin, Vienna, Hamburg, and Munich and also appeared regularly in smaller cities ranging from Aachen to Zagreb.

The successes of these troupes laid the groundwork for later groups, like Foote’s Afro-American Company in 1891 (including Marie Selika and Samson Williams, at left) and the Black America Company in 1896. These were also organized by white impresarios, but all of these large troupes provided immediate opportunities for members to take control of their own performing. Already in the early 1880s but more regularly from the late 1890s, there was an ever-increasing number of smaller groups of African-American performers circulating around and through the German lands. Their popularity increased along with the popularity of American music and dance forms after the turn of the century, as many of these were associated with African Americans. By 1914, Black entertainers were a frequent presence in major cities like Berlin, Vienna, Hamburg, and Munich and also appeared regularly in smaller cities ranging from Aachen to Zagreb.

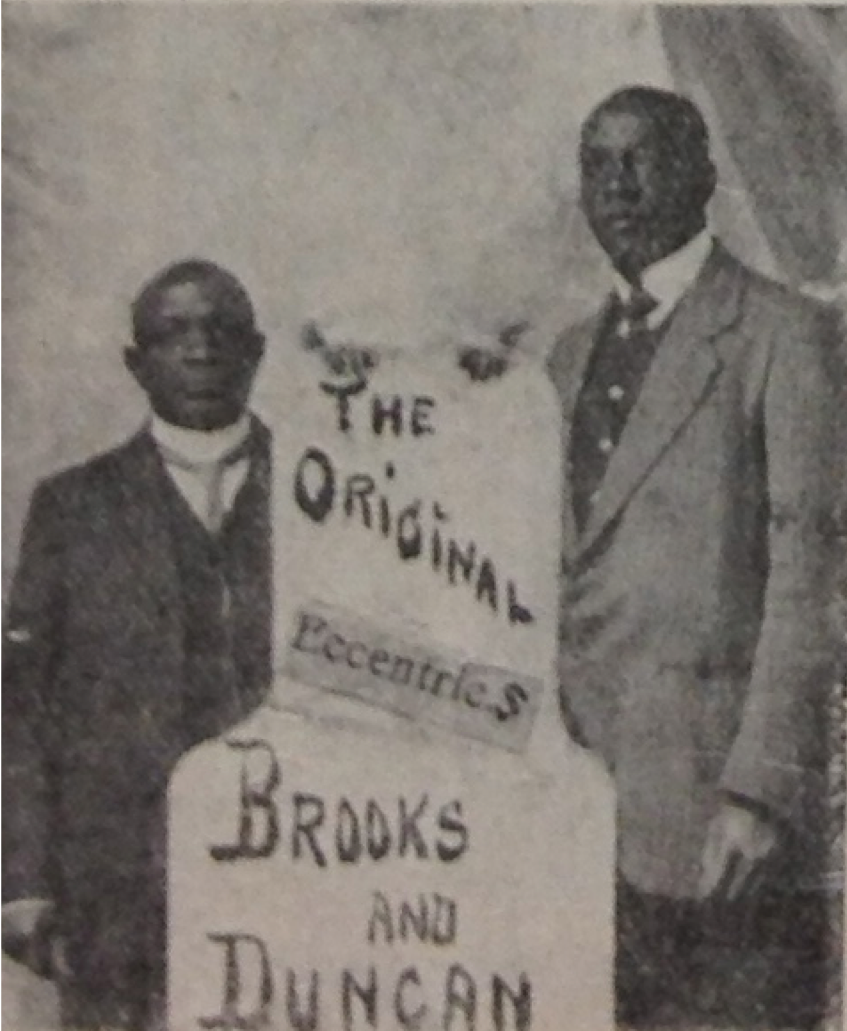

They performed in the widest range of styles, defying easy categorization. There were comics and clowns like Edgar Jones or Billy Brooks and George Duncan (right), concert singers like Sissieretta Jones, dancers like Dora Dean Babbage and Charles Johnson, and instrumentalists like Sarah Bowman and Pete Hampton or Will Marion Cook’s Nashville Students.

Most of these performers were African Americans, although some, like the Black British singer Josephine Morcashani (left), took on an American persona. In their various ways they performed versions of American Blackness and played with audiences’ racialized expectations, drawing regular attention from satirists and cultural commentators. As such, these provocative performances were an important part of a broader debate about race, nation, culture, and modernity taking place within German and Austrian popular culture.

Most of these performers were African Americans, although some, like the Black British singer Josephine Morcashani (left), took on an American persona. In their various ways they performed versions of American Blackness and played with audiences’ racialized expectations, drawing regular attention from satirists and cultural commentators. As such, these provocative performances were an important part of a broader debate about race, nation, culture, and modernity taking place within German and Austrian popular culture.

This mapping project is part of an ongoing book project, and I welcome any feedback. I also encourage anyone interested in the topic to do their own research by looking into their local newspapers, especially if you see performers where you live. If you find entertainers not shown here, please let me know the details and I’ll make sure you’re credited in the map.

Data

The data used to build this map was drawn from a wide range of sources, most notably trade journals and other periodicals but also memoirs, travel reports, private archives, and numerous secondary sources. As I note below, I am indebted to other scholars, Rainer Lotz above all, for foundational work that I have been able to build upon.

It has been challenging to find many of the performers identified in the map. On the one hand, this is true of all popular performers from the era. Although some big stars, like Otto Reuter, left an enduring legacy, most performers disappeared into obscurity. Their performances ephemeral, we have to look for scattered traces of them in newspaper advertisements and reviews or the postcards gathered by collectors and archives. But even these can be unreliable. When theaters advertised their variety programs, they did not often list every single act on the stage, and many postcards lack names and dates. Performers often provided their touring details in the trade journals of the day, but sometimes they only named a venue as a place to send their mail and sometimes their plans changed.

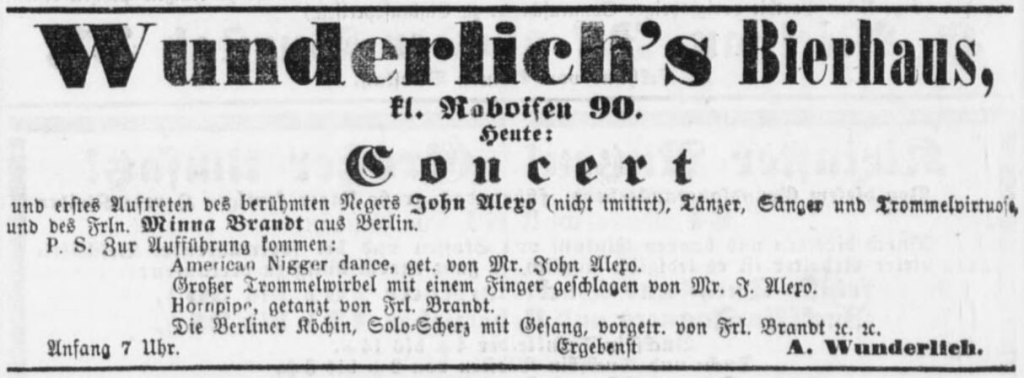

On the other hand, there are challenges particular to finding Black performers. Most obviously, it is often not clear from the names and descriptions in a printed program whether any of them are Black. Black performers were usually, but not always, identified using racialized descriptions like “Neger” or the English pejorative “Nigger.” To complicate matters, blackface performers were often described using the exact same terms and were often billed ironically as authentic.

Take John Alexo, who performed in Wunderlich’s Bierhaus (Hamburg) in April-May 1867 and was billed as a “berühmter Neger (nicht imitirt)” [famous Negro (not imitated)] who would perform an “American Nigger Dance.” On this basis, one could assume that he was a Black performer doing a minstrel act, but at this point it would have been extraordinary for a Black performer touring on his own to show up on German stages. Further, it is suspicious that Alexo shows up at the exact same time that a troupe of blackface performers (Christy’s Star Minstrels) was making a splash elsewhere in Hamburg. It cannot be ruled out that Alexo was a Black performer, but it is more likely that he was a white performer, perhaps a local, hired to capitalize on the appeal of Christy’s Minstrels. Or perhaps he was a member of Christy’s troupe who did some performing on his own. In any event, there is sufficient doubt that I could not include him, or others like him, in this database. Accordingly, I have only included those performers and performances that I have been able to verify, and I have indicated where any uncertainty remains, for example in conflicting reports on dates or venues.

This map focuses on African-American stage performances, but I have also included some “people shows.” Rather than a comprehensive rendering of the era’s people shows, I include them here when they took place in the same city and around the same time as the stage performances I am tracking. For example, in October 1891 Foote’s Afro-American Company performed a show they called “Das musikalische Afrika” [“Musical Africa”] in Berlin’s Wintergarten Theater. That same month they competed not only with the African-American comedy duo Brooks and Duncan at Kaufmann’s Varieté but also with a troupe of Azande billed as “African cannibals” at the Feenpalast. This reminds us that these entertainers all plied their trade within a field of competing performances of race and exoticism, and this can help us understand the performers’ strategies as well as the audiences’ responses.

Credits

This map, and the larger research project on which it is based, would not be possible without the foundational work of Rainer Lotz, who painstakingly pored through trade journals and other sources to establish touring itineraries for many of the performers included here. From this base I was able to survey local, national, and foreign periodicals for more details. It is worth noting that the digitization of newspapers has made it much easier to find performers who otherwise would be easy to miss in the small-print of an advertisement or a passing note of a theater review. AustriaN Newspapers Online (ANNO) is a wonderfully easy-to-use resource that is continually expanding. Unfortunately, there is no equivalent for Germany, although the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek’s Digipress does provide searching functions for many important newspapers and Europeana’s relatively clunky and unreliable system does allow for searches in some Hamburg and Berlin newspapers. Otherwise users can access digitized papers, albeit mostly without any search functions, through the Zeitschriften Datenbank and regional libraries like the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin or the Sächsische Landes- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden.

I would also like to give a very special thanks to Justin Joque and his students at the University of Michigan Library, who provided both the base code and invaluable advice at every step of putting this together.