The scholar Jean Devise has traced the earliest uses of a Moor or a Black figure in heraldry to Bavaria, the upper Rhineland, and Lower Saxony in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. The use in family and institutional crests at this time most likely reflected the spread of the imagery of the Hohenstaufen emperors, as in St. Maurice and the Black Magus, in which Black figures stood in for the universalist pretensions of the Church and the Empire.

From the early fifteenth century, in the context of increasing conflict against Muslims in and around Europe and in the context of expanding maritime exploration and global trade, including in African slaves, Black figures began to take on more fantastical, exotic, and degrading features. At this time they became a common heraldic feature across the German lands.

The examples below, from the Wolfskeel (later Wolffskeel von Reichenberg) family crest, show how St. Maurice gradually transformed from a respectable figure to a noble savage and, by the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a racist caricature.

Jeff Bowersox

Deutsch

By the early 14th century the Wolfskeel crest incorporated a Black figure bearing three roses, a symbol of the Holy Trinity. According to tradition this figure represented St. Maurice. CSvBibra, “Grabmal Wolfram Wolfskeel von Grumbach (ca. 1333),” Würzburg Dom, Wikimedia Commons.

By the fifteenth or sixteenth century one depiction of the crest had removed the saint’s clothing, while the Grumbach branch of the family dressed the figure in strikingly minimalist fashion. Scheibler’sches Wappenbuch (South Germany, ca. 1450-1580), Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Cod.icon.312c.

But most depictions did not depart from the original, fully clothed St. Maurice, although in some versions the quality of reproduction meant that the figure was reduced to a Black silhouette with uncertain clothing. Johann Siebmacher, New Wapenbuch, 2nd edition, (Nuremberg, 1612), Bayerische Staatsbiliothek, 1080914 Herald. 139-1.

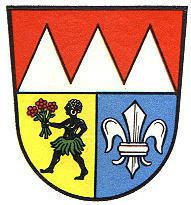

By the nineteenth century, the Wolfskeel figure had become a half-naked noble savage, complete with grass skirt. The skirt has a similar profile to the tunic St. Maurice formerly wore. Konrad Tyroff, Wappenbuch des gesammten Adels des Königreichs Baiern, vol. 4 (Nuremberg, 1821), Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Bavar. 2621 o-3/4.

In a caricatured form drawn from advertising images, the Wolfskeel figure was taken up in the crests of numerous towns and cities in the area around Würzburg, including Uettingen where the family castle is located and (until 1974) Würzburg itself. Friedrich Zech, “Wappen Landkreis Würzburg” (1956), Wikimedia Commons.

St. Maurice becomes a savage and a caricature on a family crest (ca. 1345-present) by Jeff Bowersox is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at https://blackcentraleurope.com/who-we-are/.