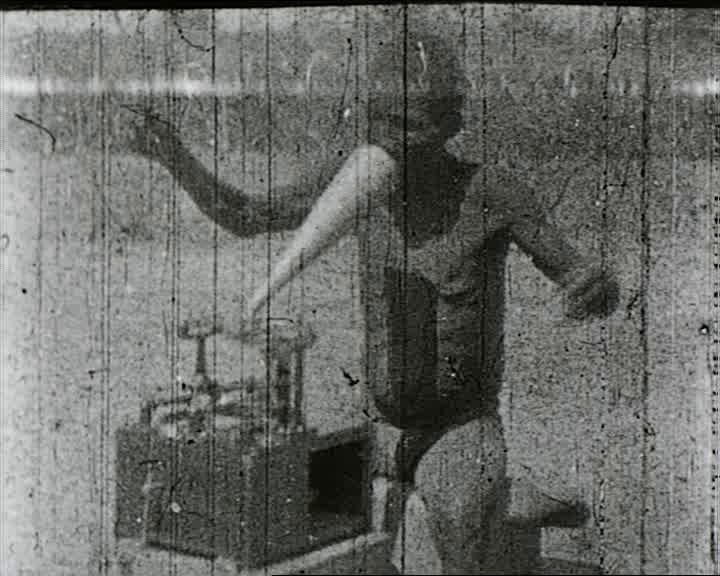

This still is taken from a film by Rudolf Pöch, which was taken during an expedition to the Kalahari desert in 1907-1909. Pöch undertook journeys to India, New Guinea and southern Africa as an ethnographic filmmaker. He was one of many, mostly amateur scholars who sought to create authentic records of peoples and cultures they presumed to be disappearing. Like photography, film offered the illusion of actuality but with the added benefit of being able to capture motion for study, which meant that they could document physical features as well as cultural practices. Their efforts were made possible by colonial networks and the colonial state, and when shown in cinemas, schools, and private and organizational settings, their work allowed viewers a vicarious experience of empire. At the same time, as Wolfgang Fuhrmann argues, these filmmakers were motivated by more than ideology; their commercial and scientific interests and often chaotic practices produced works that could also unintentionally reveal the contradictions and tensions of colonial rule.

The man in the three-and-a-half-minute video is named Kubi, and we know very little about him except what was recorded in Pöch’s notes. He was over sixty years old and apparently lived in British Botswanaland, between the Kubi Plain and K-au (Kamelpan), where the filming took place on 23 August 1908. He speaks into the phonograph in the ts-aukhoe language. Initially, Pöch had only intended to record his voice in the phonograph, but he was so impressed by Kubi’s vigorous gesticulations that he decided to film him as well.

Pöch’s notes tell us that Kubi is telling a story about how elephants behave at watering holes. Kubi explains that there once was more water in the plain, which then drew more elephants to drink and bathe before returning to the bush. He points in the direction of the plain and then explains where there once were elephant paths. He then goes on to describe an occasion when he was almost killed by elephants. Unfortunately the details are not provided, as Pöch was more interested in Kubi’s excited hand gestures

As in this film, a common theme in depictions of colonial life was the encounter between colonial subjects and technological innovations. As Assenka Oksiloff notes, this provided a way to refer to the presumed evolutionary gap between white Europeans and others around the world, especially Blacks. Such depictions often showed the non-white figures confused, astonished, or amused, but the gap could also be suggested, as in this case, simply by juxtaposing “primitive” dress and “modern” technology. The filmmakers’ subjects are thereby reduced to a mere object of study, a representative of an ethnic or racial “type” (in this case of a “Bushman”) and not an individual in his or her own right. The involvement of the filmed subjects or other locals in the creation of these films was considered unimportant and usually edited away where it was evident. Like “people shows,” such films provided viewers the illusion of an unmediated encounter with the wider world, but with films it was much easier to control the message conveyed through that encounter.

Incidentally, the clip is noteworthy for being the oldest surviving film to be synchronized with a simultaneous recording of the human voice. Pöch recorded the audio and visual material at the same time but with separate devices, and we have the Austrian film scholar Dietrich Schüller to thank for bringing the two media together for the first time in 1984.

Jeff Bowersox

Deutsch

Source: Rudolf Pöch, Buschmann spricht in den Phonographen (1908), Österreichische Mediathek / Austrian Media Library vx-01934_01_k02. ©Österreichische Mediathek.

Kubi speaks into a phonograph (1908) by Jeff Bowersox is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at https://blackcentraleurope.com/who-we-are/.