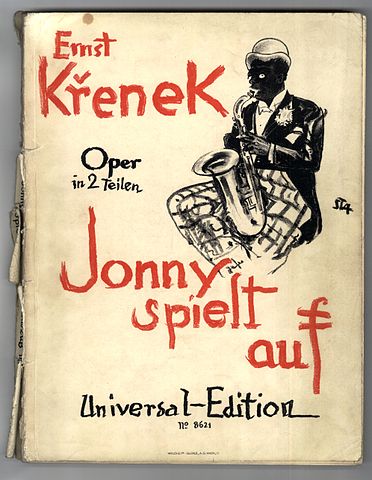

Ernst Krenek’s 1927 “jazz opera” Jonny Strikes Up [Jonny spielt auf] pits an African-American jazz musician (Jonny, played in blackface) against a modernist white German composer in a battle for the future of popular music. The show was a critical and popular success across Europe in the late 1920s both because it tapped into a contemporary vogue for jazz and, as Jonathan O. Wipplinger convincingly suggests, because its contradictory presentations of African-American culture allowed for a wide range of readings and appropriations over decades. The fact that Krenek’s score actually contained very little jazz, and what “jazz” it presented actually bore little resemblance to what jazz musicians were playing at the time, was beside the point.

Jonny‘s success made it a lightning rod for the radical right, who saw an opportunity to raise the profile of their critiques of the Weimar state. As they also did in protests against Josephine Baker’s performances, they tried to link debates over jazz and cosmopolitanism to widespread resentment over the terms of the Versailles Treaty. In particular, by connecting these shows to the use of colonial soldiers in the Rhineland occupation, they hoped to fill out a much broader narrative of national betrayal and racial degeneracy. The lasting resonance of Jonny in these efforts can be seen in the infamous poster for the Nazis’ 1938 exhibition on degenerate music, which was based on the illustration above.

In the newspaper review below, a Munich commentator named Niedermeyer reports on a protest by Nazis at the show’s premiere. They tried to drown out the performers with boos and to stop the show with smoke bombs and tear gas. Nevertheless, most of the audience insisted on seeing the performance through after the police eventually removed the protesters. Niedermeyer draws hope from the broad resistance to such disruptions from the cultured classes, but his disappointment at the director’s pandering and the slow police response provides a chilling note of what is to come.

Jeff Bowersox

Deutsch

“Johnny” unleashes scandal in Munich.

The opera Jonny Strikes Up [Jonny spielt auf] by Krenek, which has produced lots of talk since the last winter season, has now also been performed in the Munich Gärtner-platz-Theater after the Bavarian State Opera showed no interest in taking it on. Even before its performance one could find in newspapers protests that drew a connection between the figure of Jonny the Negro jazz musician and the “black shame on the Rhine,” a connection that is hard for a fair-minded person to understand. Jonny had hardly taken the stage in the premiere before a minority of some ten people, who obviously belonged to right-radical associations, began with a lively round of boos. A stink bomb attack soon followed; they also didn’t forget tear gas bombs. The performance had to be interrupted because, in the fearsome noise made by the disturbers of the peace, the singers could no longer make themselves heard and were also prevented from further singing by the effects of the gas. Several audience members fainted and had to be carried out of the theater by staff. However, the larger part of the public stayed in their seats with handkerchiefs over mouth and nose and thereby made sure the performance would carry on despite the disruptive intentions of the swastika-types. Quite late, the police intervened and removed the ringleaders.

The artistic success of Krenek’s opera was, however, not so pronounced. Director Warnecke had carefully softened all the powerful and pointed scenes so that the greater part of the effects fizzled out from the start. The main roles were held by outsiders. Alfred Jerger from the Vienna State Opera played Jonny, the Berliner singer Oestvig played the composer, and the Leipziger Horand played Daniello. Chamber singer Gertrud Bender from the Stuttgart Regional Theater lent her charm to the role of Ivonne, Elisa Stünzer from the Dresden State Opera took on the role of the singer Anita with stylish virtuosity. Naturally the play suffered considerably from the disturbances. The orchestra was directed by Professor Mikorey as well as possible; the musicians did their best to do justice to Krenek’s atonal music, which was unfamiliar to them.

Above all, regarding this Jonny-scandal it should be said that at the time it seemed that all of the interested circles of artist and general public energetically took a stand against the unhealthy trend of disturbances and unilateral efforts to judge art, as is happening again and again not just in Munich but indeed in Bavaria as a whole. Among the most conspicuous of these was the very sabotage of Ufa’s Meistersinger films. It doesn’t fail to leave a surreal aftertaste that the swastika-types see in Jonny Strikes Up a sort of foreign-political danger that, that they associate in this operetta Negro [Neger] a so-called black danger, that they associate this operetta Negro [Neger] with the whole so-called black shame on the Rhine. These hot-tempered lads should consider that, in the end, their behavior only serves to advertise the very work they’re protesting.

Niedermayer.

Source: Niedermeyer, “‘Jonny’ entfesselt Skandal in München,” Der Artist 2221 (14 July 1928). Translated by Jeff Bowersox.

Nazis connect “Jonny Strikes Up” to the Black Shame (1928) by Jeff Bowersox is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at https://blackcentraleurope.com/who-we-are/.