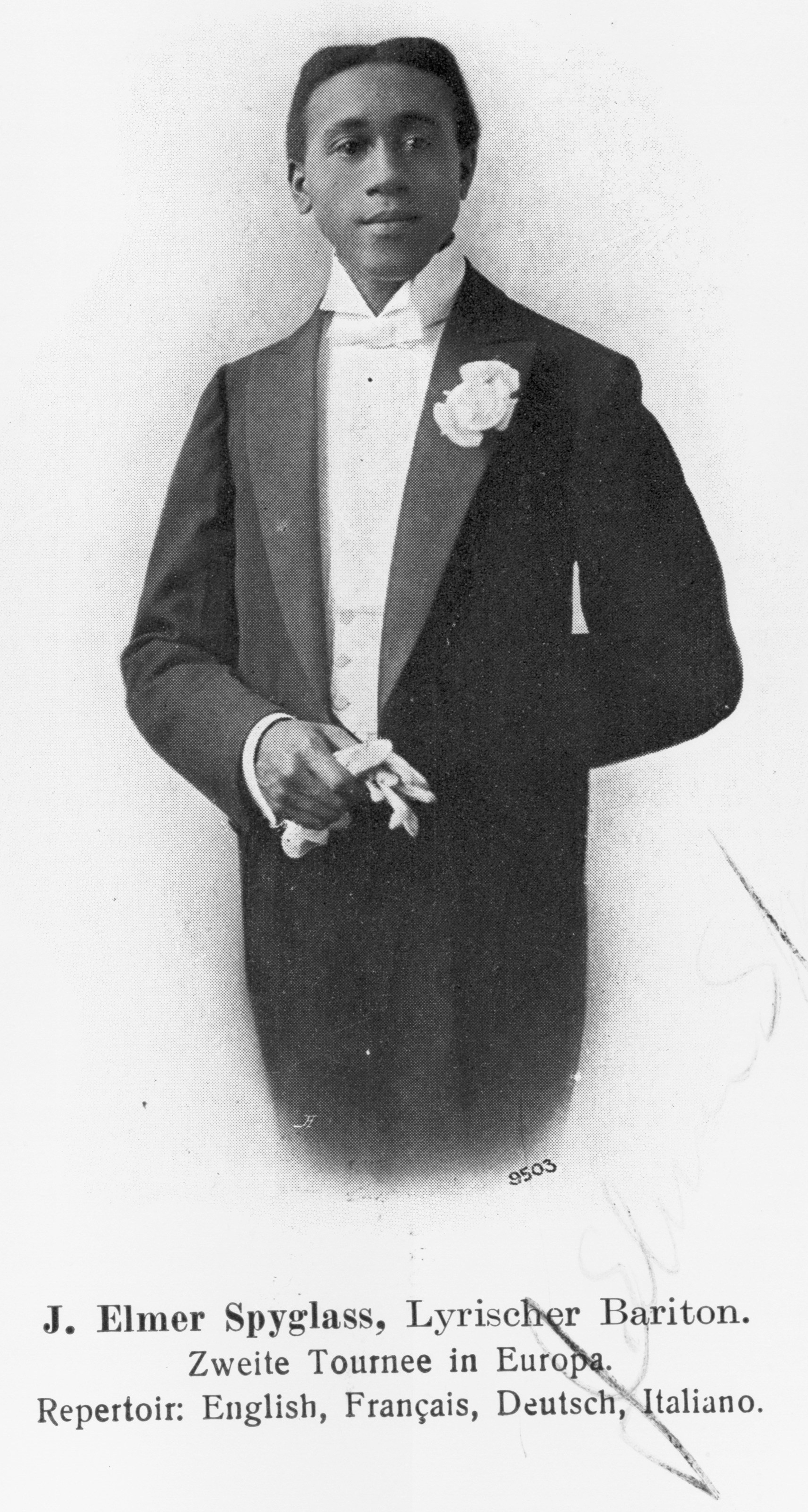

J. Elmer Spyglass (ca. 1877-1957) was an African-American musician who pursued his career in Europe before the First World War and eventually ended up in Germany, where he lived until his death in 1957. Like many African Americans, he tried to make his way as a concert singer, but few black artists were able to overcome the resistance to seeing them as serious musicians. Instead he found his way into music halls and cabarets, performing with established white stars all around Europe and learning several languages along the way. Like many African-American entertainers, in his acts he brought together “African American” pieces, like spirituals and folk songs, with works ranging from opera to European folk music. He was successful enough that at the age of 53 he retired from the stage and took up residence in a pension in a Frankfurt suburb, where he lived with his white German partner Helene Patt. They also had a flat in the nearby village of Schwalbach am Taunus, which they visited regularly.

He did not leave when the Nazis came to power. Because he was a well-known figure locally and was not particularly political, he said he never had much trouble with the authorities, despite being both American and black. In 1944 Spyglass and Patt were bombed out of their Frankfurt residence and moved to Schwalbach, where they helped locals to get through the war. When American troops arrived, Spyglass served as a mediator between the townsfolk and the occupying authorities and gave English lessons. In 1954, the town recognized him for his services by making an honorary citizen and in 1994 established in his honor a prize recognizing individuals who had worked toward intercultural understanding.

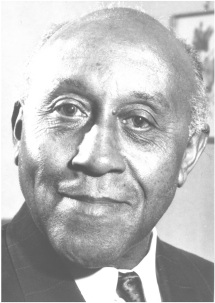

Inspired by a desire to bring together Germans and Americans, Spyglass returned to work as the receptionist in the U.S. General Consulate in Frankfurt. It was in this capacity that he drew the attention of journalists, who were captivated by his story. In this interview published in the American illustrated magazine Life, Spyglass’s extraordinary experiences provided an opportunity to show that the transition to democracy might not be so difficult for the Germans after all.

Jeff Bowersox

deutsch

J. Elmer Spyglass: Ex-cabaret singer helps teach Germans about the U.S. and its democracy by Will Lang

Frankfurt

The best salesman for American democracy in Germany today is an aged Negro who has not lived in his native U.S. for 41 years. He is J. Elmer Spyglass, a man whose career is as unusual as his name. A singer, Mr. Spyglass retired in 193- after two decades of concert and music-hall success all over Europe. Now, 70 years of age and unmarried, he has decided to spend his remaining years serving his country as a receptionist at the U.S. consulate in Frankfurt.

The Frankfurt consulate is one of the busiest in Europe. Tending American interests in the whole of western Germany, it is visited by thousands of Germans seeking news and help from American relatives; it has repatriated hundreds of Americans trapped in Germany during the war, and it hears to pleas of innumerable displaced persons who hope somehow to reach America.

Mr. Spyglass sees them all. His pleasant, coffee-colored face greets everyone who comes to do business with the U.S. Even the most excitable person is disarmed and charmed by the gracious receptionist who can speak to visitors in any of five languages. Mr. Spyglass often answers their queries himself, thus sparing the small and hard-working consular staff. When he cannot, he steers the visitors to the proper office in the consulate. He manages to preside over his bustling way station with the poise of a veteran actor. He considers it his function not only to be cordial to visitors but to keep the show moving.

Consul General Sydney B. Redecker says of Spyglass: “We have only 15 officers to handle all of this business, and Elmer relives us all by the way he handles visitors. More important, he is a wonderful ambassador of democracy, especially with the Germans.” Mr. Redecker is one of few who address the colored man as “Elmer.” To others he is known respectfully as “Mr. Spyglass.”

●

The tricks learned on the European stage are useful to Mr. Spyglass in dealing with the daily traffic of consulate visitors. Many Germans are apt to be nonplused when stopped by a Negro receptionist speaking flawless German. But Mr. Spyglass has met this situation in innumerable cabarets and supper clubs during his career. Using such old-fashioned, courtly phrases as “Dear lady” or “Pray be seated,” he flatters the most excitable into the nearest chairs, after which they calm down and tell their stories.

The Germans who confide in Mr. Spyglass would exasperate anyone with less patience. Many, wishing to write to relatives in America, come to the consulate to find the important street addresses and cities where those relatives live.

“There are more than 25 million Germans-Americans living in the U.S.,” Mr. Spyglass reminds them.

“Yes, but our relatives live in America. You are the American consulate. You should know where they live!” the Germans insist.

At this point Mr. Spyglass is kind but firm. “I’m very sorry, but we’re not allowed to search for such things,” he says and directs them to the Red Cross.

Many Germans who once lived in the U.S. now want to re-emigrate. “To those who lived in America only a short time, not long enough to take our citizenship papers,” Spyglass says, “I give some hope of getting back. But to those who lived there for 10 or 15 years without bothering to apply for papers I don’t give much hope. Of course no one has ever given me any instructions for dealing with them; those are just my feelings.”

This is the reasoning to be expected of an ambassador rather than a receptionist, but Mr. Spyglass is on safe ground; the present U.S. quota for German immigration is 26,000 a year, but in these postwar years only “petition cases” are accepted – husbands and wives, fiancees, dependent children or parents of American citizens in the U.S.

For a long while last year American soldiers wanting to take their German finacees or brides to the U.S. added considerably to Spyglass’ problems. He became adept at spotting the fraternizers – GIs who loitered bashfully in the lobby if the reception room was full or who stammered awkwardly when Mr. Spyglass invited them inside:

“I wanna see the consul!” the soldier blurts.

“What about?” asks Mr. Spyglass.

An agonizing silence, then the soldier says weakly “I wanna take my girls home.”

On these occasions Mr. Spyglass exuded an atmosphere as intimate as the confessional booth. “When they come so bashfully, I know what they’re after,” he says. “But sometimes I just have to pull the words out of their mouths.”

●

Spyglass claims Yellow Springs, Ohio as his home town. His blacksmith father had some Spanish blood, which may explain the unusual name. A choir boy in Yellow Springs, young Elmer went to Europe in 1906 to continue his voice studies. He had already graduated from the Toledo Conservatory of Music and was the first Negro to conduct in the Carnegie Music Hall, in Pittsburgh. Friends had raised $400 to send him abroad. That was a lot of money in those days, but it proved not enough to pay for expensive European teachers. Mr. Spyglass soon turned to music halls and cabarets and struck success with his first engagement. With a repertoire of American and European songs he toured France, Italy, Belgium, Austria, Hungary, Romania and Germany, where he established a home in Frankfurt am Main.

During the war the Nazis caused him no trouble, despite his membership in an “inferior race.” Mr. Spyglass is still not sure why. “Perhaps i was because I had lived there off and on since 1907,” he says. “I knew all of old Frankfurt, from the bank directors down to the police. And I never mixed in politics.”

●

The “ambassadorial” work of the receptionist is not confined to his desk in the consulate. From his apartment in Schwalbach, a village within commuting distance of Frankfurt, Mr. Spyglass has attacked the “German problem” in his own way. Shortly after the armistice many Germans came and asked him for English lessons. While it was obvious that most of them wanted to equip themselves for jobs with the Americans, Mr. Spyglass saw beyond the obvious and willingly shouldered the job. At one time he was teaching as many as 200 German adults from nearby villages; he still conducts two classes in English each evening. “I think that the more people know about English, the more of a help it is to my country,” he says.

J. Elmer Spyglass has become the symbol of American democracy in Schwalbach and the surrounding countryside. At his birthday last year almost the entire town sent flowers to his apartment. Flowers filled the tables and most of the floor, and bouquets were pinned all over the walls and lace curtains. Dozens of German children, his students, trooped in with modest presents of fruit and vegetables. The Kinder then sang songs in English that the old man had taught them. There, far away from the U.S., they greeted his birthday with Swing Low, Home, Sweet Home, My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean and My Old Kentucky Home.

Source: Will Lang, “J. Elmer Spyglass,” Life (3 November 1947), 4-11.

J. Elmer Spyglass teaches Germans about democracy (1947) by Jeff Bowersox is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at https://blackcentraleurope.com/who-we-are/.