The early thirteenth-century romance Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach features several African characters. Perhaps the most intriguing is Feirefiz, the mixed-race son of Parzival’s white Christian father, Gahmuret, and the Black pagan queen, Belkane. Wolfram marks Feirefiz’s mixed parentage by giving him mottled Black and White skin “like a magpie.” These unusual features have presented complications for illustrators over the centuries, and, while there are varied artistic depictions of Feirefiz, he is often not included in illustrations of the text. These images are taken from Engelmann’s 1888 illustrated children’s version of Parzival. Engelmann does not include Belkane in his version, but he does introduce Feirefiz at the end of the tale, when he comes to Christian Europe in search of his father but instead encounters his half-brother Parzival. Contrary to what one might expect, the book and its images do not directly reflect the racism of the colonial era but instead reflect more the sentiment of the medieval text.

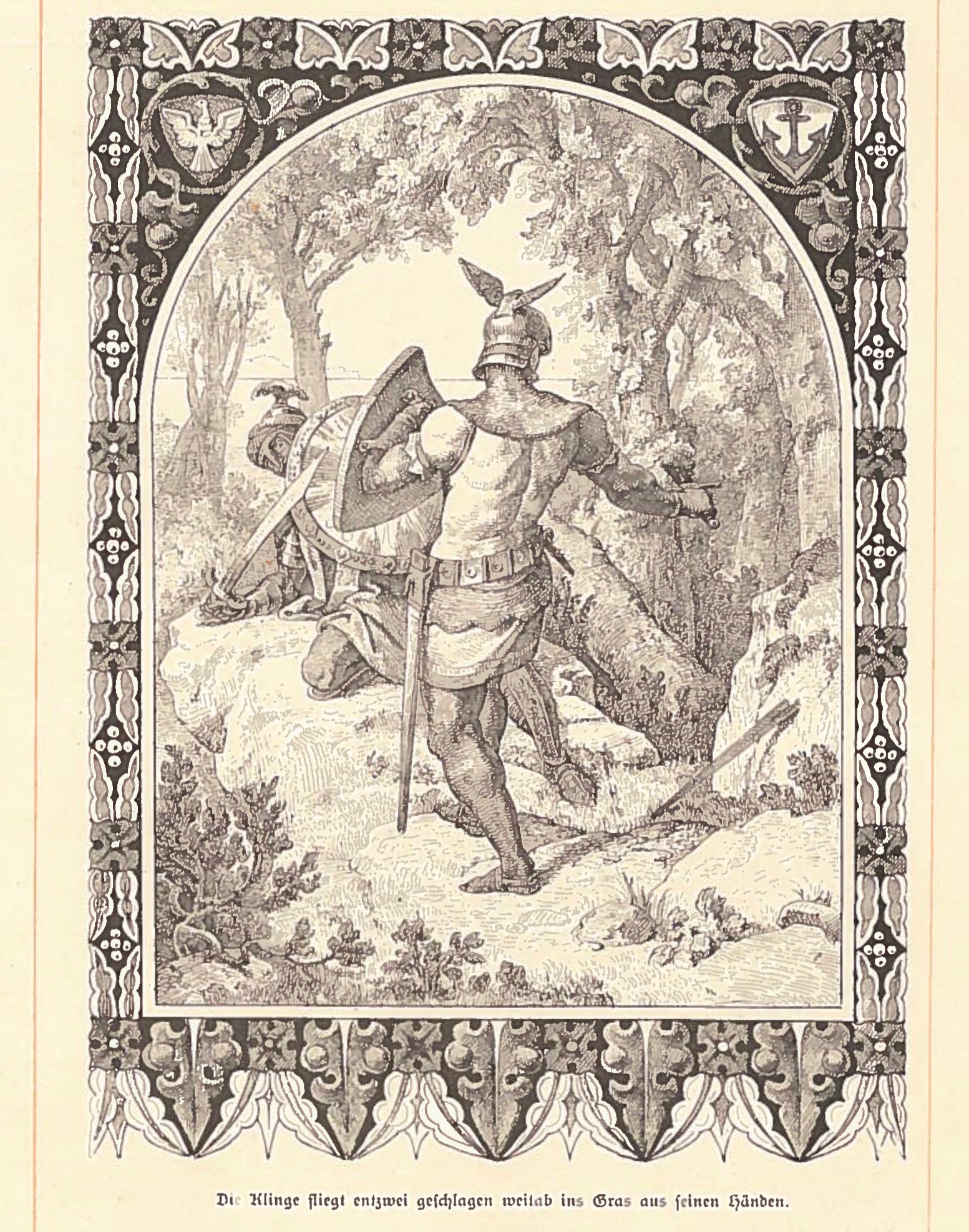

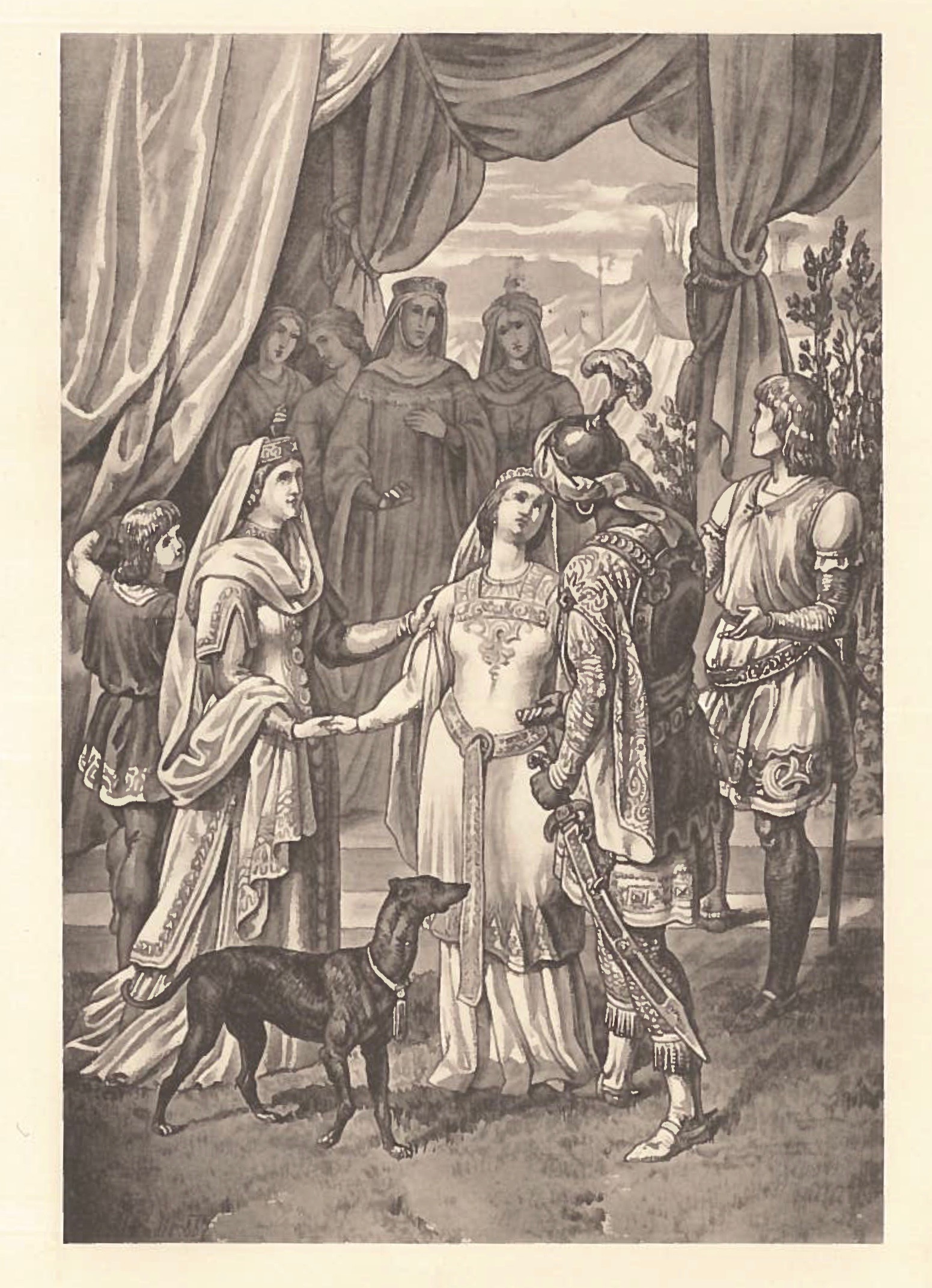

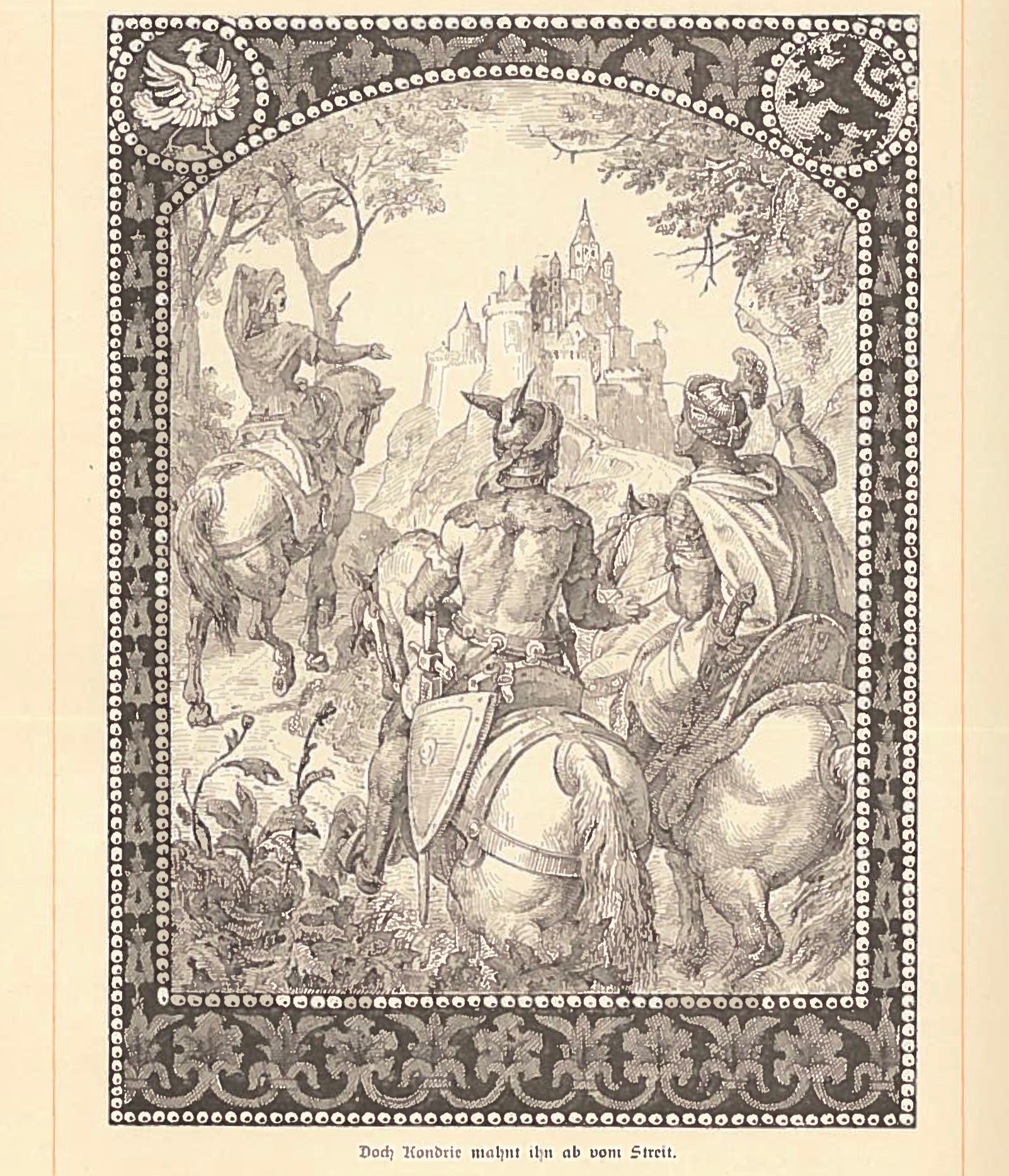

Engelmann’s depiction is remarkable since many modern versions—most notably Wagner’s Parsifal—exclude both Feirefiz and his mother altogether. In these images Feirefiz is identifiably Black, with dark skin and characteristically short, tightly curled hair. He has no visible light patches on his body, although not much of his skin is visible in general and his face is never fully shown. He is given other distinctive markers associated with Saracens: a turban-wrapped helmet, a scimitar, and a gold hoop earring in one ear. It is unclear why Feirefiz is depicted as simply Black, but perhaps, his accessories offer some clues. They suggest an exoticism recognisable in contemporary depictions of non-white men and identify him as an archetypal non-white foreigner. Perhaps the absence of Feirefiz’s light skin suggests a reluctance to reconcile this foreign Black half with Feirefiz’s white Christian half, an uneasiness with miscegenation characteristic of the era.

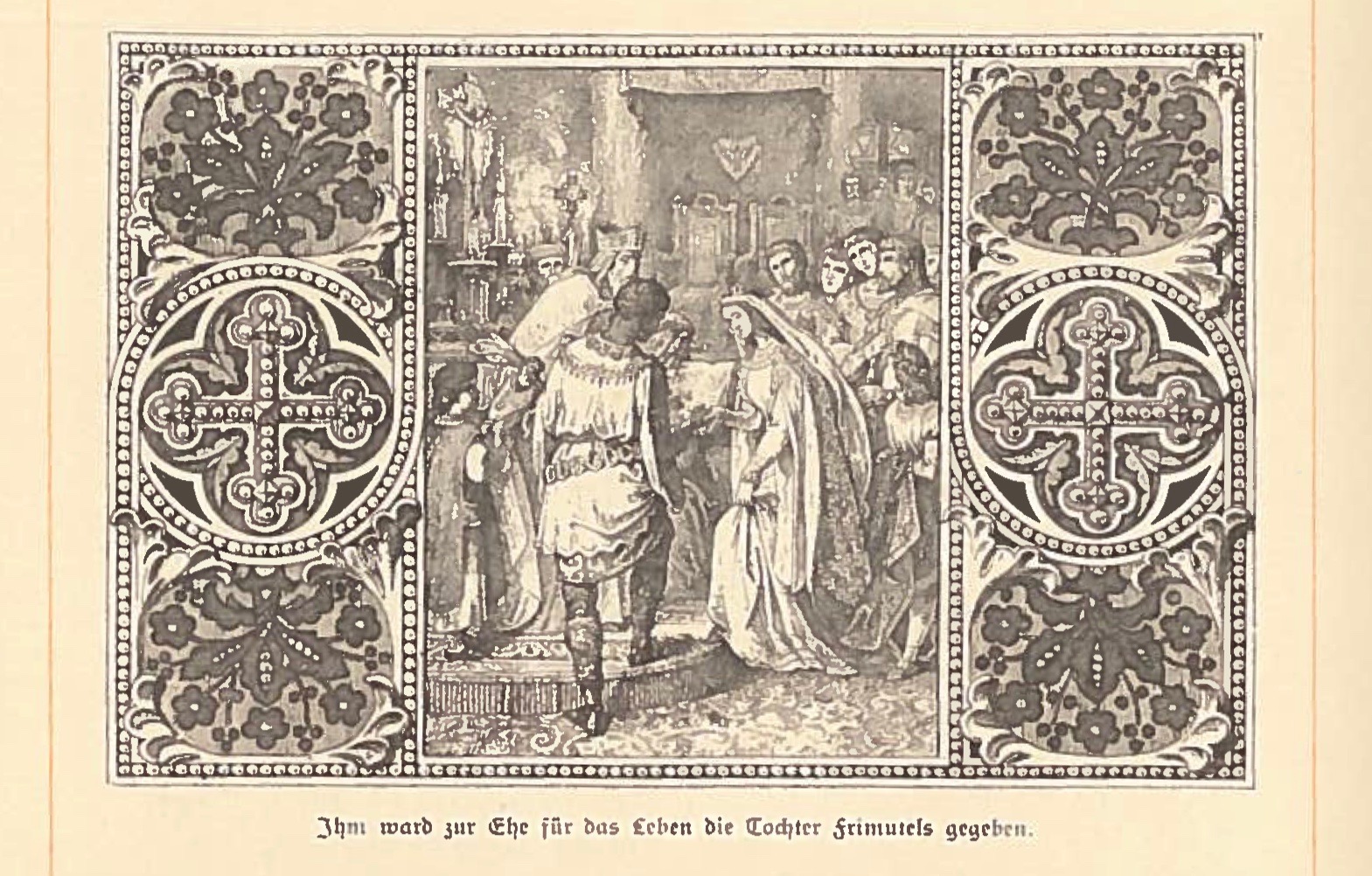

Nevertheless, it is important to note that Feirefiz is not depicted as characteristically different from the other knights; as they do with other white knights, courtly women swoon over him, and one image shows him marrying the white Repanse. In this image their white and Black hands meet clearly in the center of the image as a sign of their union. Like the medieval text, Engelmann’s version of the story depicts Feirefiz as an ‘honourable heathen’ and does not describe him in otherwise derogatory language.

The images and corresponding text of Engelmann’s Parzival exemplify a continuity between the depictions of the medieval period and the colonial period which may seem surprising, especially considering other artistic representations of the Parzival text from the late nineteenth century. For example, Wagner’s erasure of Black characters from his 1882 Parsifal is perhaps the result of Wagner’s known racism. A painting of Parzival and Feirefiz in Neuschwanstein castle, on the other hand, depicts Feirefiz as lighter-skinned—perhaps as Middle Eastern and Muslim—with barely visible black spots on his face. Engelmann’s depictions thus stand out. They are possible because Engelmann remains close to a text predating the era of scientific racism and its subsequent visual and literary depictions.

Isobel Sanders

deutsch

Source: Emil Engelmann, Parzival. Das Lied vom Parzival und vom Gral (Stuttgart: Paul Neff, 1888).

Depicting Feirefiz in the age of empire (1888) by Isobel Sanders is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at https://blackcentraleurope.com/who-we-are/.